There are many people pointing out the similarities between the bursting of the Japanese bubble in the 1990s and the situation in China today. I’m often one of them. So when I read Yi Fuxian’s piece on the topic on Project Syndicate, I was not expecting to have it make me think of the current state of the US, but here we are.

Japan’s housing bubble was preceded by sharply rising ratios of home prices to annual income, with Tokyo’s surging from eight in 1985 to 18 in 1990. This trend was driven by a number of factors, including Japan’s land-tax policy, financial deregulation, and poor coordination of fiscal and monetary policy. But demand from first-time homebuyers – aged 39-43, on average – also made a substantial contribution.

Because homeowners felt wealthier, they consumed more. This drove up the prices of goods, services, and stocks, leading to more jobs and less unemployment. But demand for new housing soon began to fall, and demographic shifts were a key factor. In 1991, as the share of Japan’s population aged 65 and older reached 13%, the number of first-time homebuyers began to decline. Property values plummeted, the stock market collapsed, and Japan fell into a deflationary trap, characterized by falling fertility and rising unemployment.

A misdiagnosis of the problem made matters much worse: what was actually a chronic demographic disease was treated as an acute illness. Policymakers believed that Japan was grappling with yen appreciation as a result of the 1985 Plaza Accord, under which the world’s major economies agreed to devalue the dollar. So, to stem the currency’s rise, they printed money, lowered interest rates, increased the government deficit, and engaged in quantitative easing.

These policies, together with the rebound in the number of new homebuyers that began in 2001, caused home prices to start rising again – and exacerbated the underlying disease. As starting a family became more expensive, young people delayed marriage and had fewer children. The government tried to boost birth rates with interventions like increased child allowances and improved childcare services, but it achieved only limited success: the fertility rate rose from 1.26 births per woman in 2005 to a mere 1.45 a decade later.

At that point, then-Prime Minister Abe Shinzō set the goal of lifting the fertility rate to 1.8. But the relevant measures – which sought, for example, to make it easier for women to return to work after giving birth – could not offset the effects of the accommodative monetary policies that were viewed as vital to combat deflation and stimulate economic growth. Home prices continued to soar, marriages declined further, and births plummeted. Last year, Japan’s fertility rate amounted to just 1.15 births per woman.

To be fair, this all actually does apply to China, but I think it applies to most of the developed world as well. Fertility rates are dropping everywhere, and nobody can explain why. There is no way that this article is the monocausal explanation, but as a young-family-haver myself, I can say that I’m feeling the housing squeeze.

The US economy is increasingly reliant on consumers spending out of increased wealth — primarily because the stocks and houses they own keep going up in price even though households are not really borrowing and their wages are increasing slowly. This means that it increasingly becomes a policy goal (whether stated or unstated) to keep stock and house prices high; if either were to fall, a recession would soon follow. If house prices remain high forever, though, there becomes a set of haves (people who already own houses) and have-nots (those who don’t). And as it tends to be the older generations who already have houses and the younger generations who do not, the generation who are expected to be starting families are more and more have-nots.

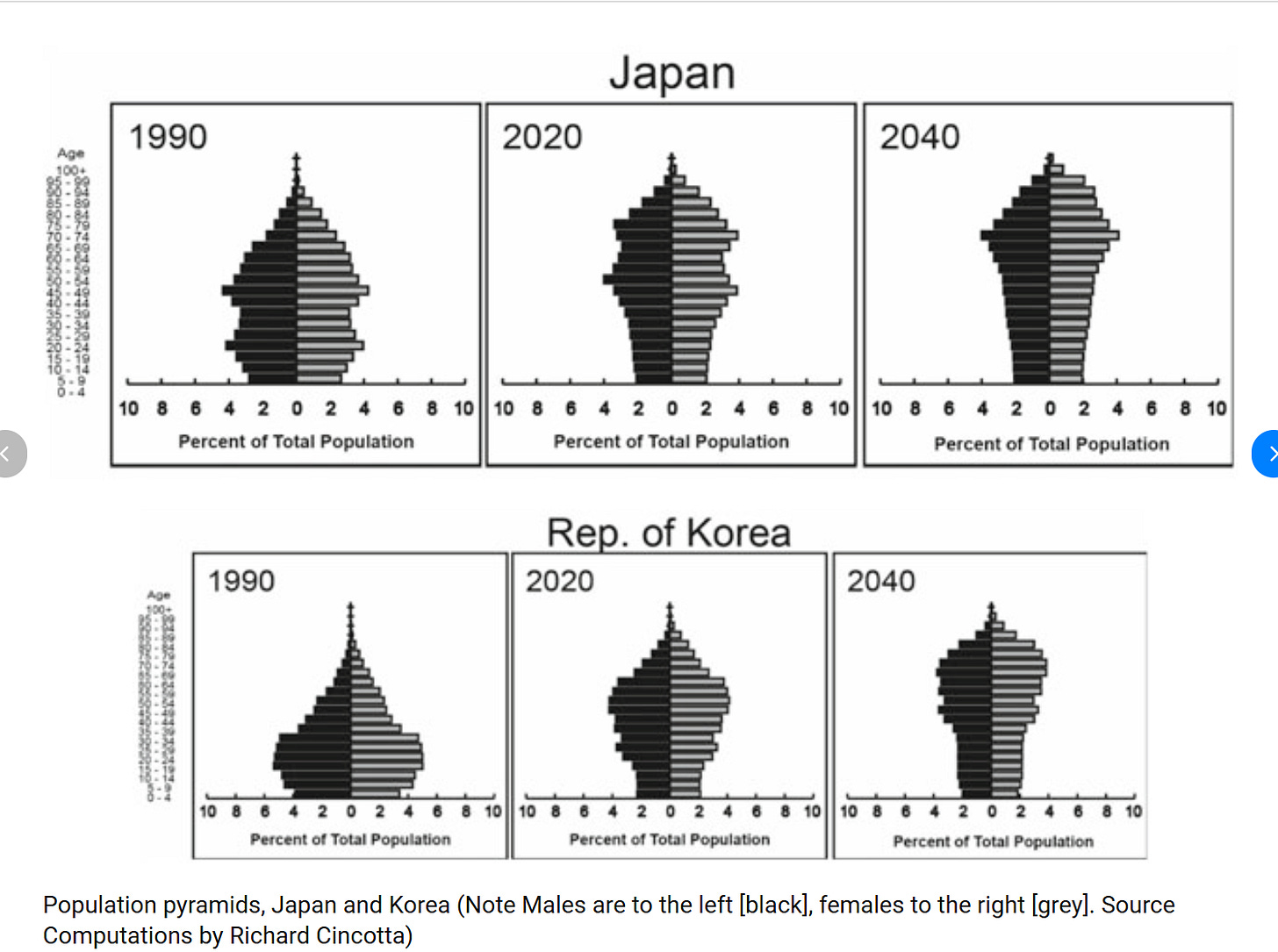

That sort of thing leads to your population looking like this:

So while monetary policy driving up the cost of housing is definitely not the only thing driving falling fertility rates in the developed world, it’s not helping either.